These include Catholicism and the legacy of Irish nationalism, the inward sufferings of gay people throughout most of history, and difficult emotional currents within families.

Tóibín, it should be added, has serious interests. It also aims to depict complicated feelings and interactions with a minimum of fuss and portentousness, using simple words and a precisely controlled tone that implies a certain hush. His fiction works hard to create the illusion that the characters reveal themselves almost independently of the narrating voice. But in his novels, on the whole, he's so intent on leading his readers where he wants them without letting them catch him doing it that making them laugh too often might strike him as counterproductive. Tóibín's writing isn't humourless there are darkly comic scenes in The Master and some witty lines of dialogue in The Blackwater Lightship, and his journalism is frequently very funny.

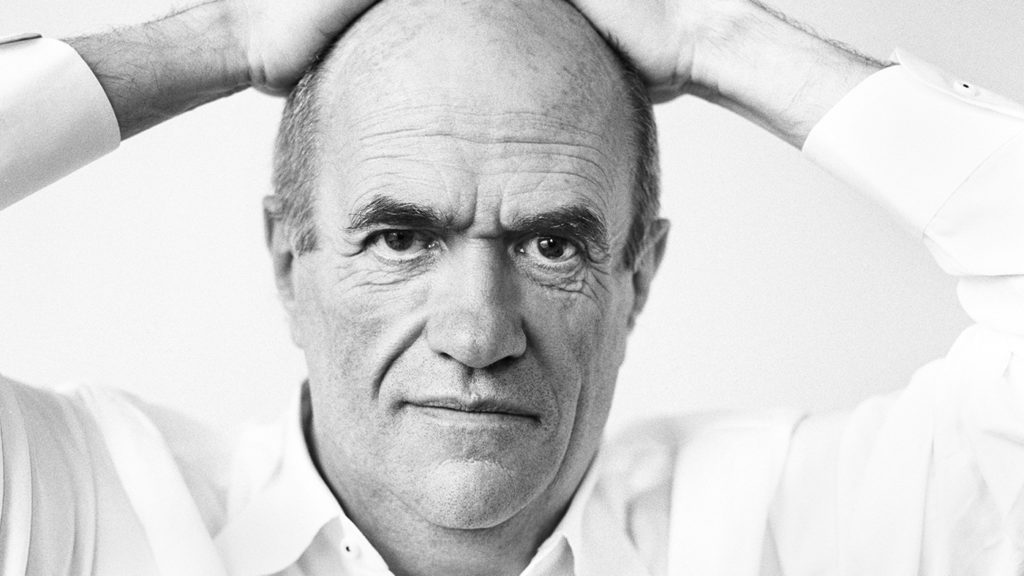

O ne of the striking things about Colm Tóibín, perhaps the most admired Irish writer to emerge since John Banville, is the feeling in his work of a powerful sense of humour being strategically suppressed.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)